From a sandy terrace above the west bank of the Rio Grande, about 35 miles south of Socorro, the scrub desert stretches out for miles to the distant mountain ranges.

It’s a lonely and desolate place baked by a hot sun in summer and chilled by snow-laden storms in winter. It’s a land of dry, stunted grass, creosote and mesquite that inspired an Army officer in 1867 to call it of “no earthly value.”

Nonetheless, the Army selected this harsh land as the site of Fort Craig, which more than 140 years ago became a strategic link in the military defensive system of frontier New Mexico.

For 31 years, from 1854 to 1885, the fort protected settlers and travelers in the lower Rio Grande Valley from raiding bands of Apaches, Comanches and Navajos.

During the Civil War, Fort Craig presented a formidable barrier to a Confederate brigade from Texas that sought to add New Mexico to the Southern sphere. A few miles north of the post, the issue was contested in early 1862 in the famous Battle of Valverde.

The Texans prevailed in the battle, routing the forces from Fort Craig, but it was merely a temporary success. Today, only a few scattered adobe and rock walls of the fort’s buildings, surrounded in part by remains of earthen fortifications, remain to mark where a stirring segment of New Mexico’s heritage unfolded.

The Texans prevailed in the battle, routing the forces from Fort Craig, but it was merely a temporary success. Today, only a few scattered adobe and rock walls of the fort’s buildings, surrounded in part by remains of earthen fortifications, remain to mark where a stirring segment of New Mexico’s heritage unfolded.

In 1851, the Army committed two blunders when it built Fort Conrad along the Rio Grande, eight miles north of the later Fort Craig.

Not only was Fort Conrad mistakenly built on private land, but it also was near a low, marshy area that proved to be unhealthy. Repeated outbreaks of malaria plagued the garrison, often leaving many soldiers unfit for duty.

As a result, Fort Conrad’s life was short. It was soon abandoned, and on April 1, 1854, Capt. Daniel Chandler led two companies of the 3rd Infantry Regiment down river to the new post of Fort Craig. It had been under construction for several months on 40 acres leased from the Armendariz land grant.

Named for Capt. Louis T. Craig, who had served in New Mexico and who later was killed by deserters in California, the new post was spacious by frontier standards.

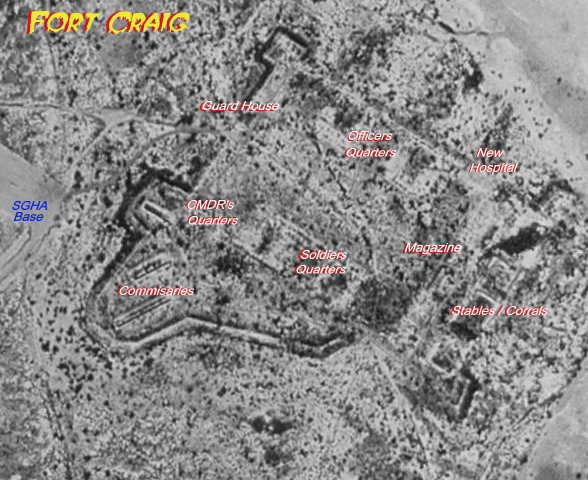

Extending 1,050 feet east to west, and 600 feet north to south, Fort Craig consisted of 22 buildings of adobe and rock construction around four sides of a large parade ground. Major structures included the commanding officer’s quarters, enlisted barracks, officer’s quarters, warehouses, commissary, ordnance sheds, stables, hospital and sutler’s store.

An adobe wall enclosed the post, and a sally port, or gate, in the west wall provided the only entrance. Surrounding the fort outside the wall was a defensive ditch, a feature unique in Southwestern frontier military posts. Craig was designed for two companies, about 120 men, but it often was garrisoned by four.

In its formative years, Fort Craig’s mission was to defend against bands of Indian raiders that plagued southern New Mexico throughout the middle decades of the 19th century. Although the soldiers took part in major campaigns against the Mimbres Apaches in 1856 and 1858, life at the post was largely a never-ending round of patrols, often-futile pursuit of small bands of raiders and an infrequent and minor skirmish.

Boredom was a bigger threat than the Apaches. A daily diet of guard mount, infantry and cavalry drill, inspections, cleaning of weapons, stable call and other routine chores weighed heavily on the garrison.

In a letter to his sister in Illinois, Pvt. Andrew Ryan, who was stationed at Fort Craig for more than a year, lamented:

“I never was in a place in my life that was so void of any news. Month in and month out, it’s the same monotonous routine from morning to night. I am horribly sick of this place. I would rather be on the march than lay around this garrison doing nothing.”

In April 1861, the outbreak of the Civil War in the East portended a more lively existence for the isolated post in far-away New Mexico.

A month after the start of hostilities, Henry Hopkins Sibley, a major of cavalry stationed at Fort Union, near Las Vegas, resigned his federal commission to follow his native state of Louisiana into the Confederate ranks.

Sibley traveled to Richmond, Va., where he won the support of President Jefferson Davis for an ambitious plan to conquer New Mexico Territory (which in 1861 included Arizona), Colorado and California. With a commission as brigadier general in the Confederate Army, Sibley set up headquarters in San Antonio, Texas, to recruit and train three regiments of cavalry— about 3,500 men. By January 1862, they were ready, and Sibley’s Brigade marched on New Mexico.

Well aware of Confederate intentions, the N.M. Territorial Legislature in Santa Fe passed the War Powers Act on Jan. 25, 1862, “to repulse and drive from our soil the now invading army.”

Gov. Henry Connally was authorized to call up the Territorial militia, which was ordered to reinforce Fort Craig, where 1,200 federal troops under Col. Edward R.S. Canby had been concentrated to await the Confederates behind new earthern fortifications bolstered by cannons.

When the militia forces, which included Col. Christopher “Kit” Carson’s 1st New Mexico Cavalry, arrived, Canby had nearly 4,000 men. In fact, the fort was so crowded that many of the soldiers were forced to pitch tents outside the walls.

Writing to Secretary of State William Seward in Washington from Fort Craig on Feb. 5, 1862, Connally was optimistic:

“I have no fears of the results here. We will conquer the Texan forces. If not in the first battle, it will be done in the second or subsequent battle. We will overcome them. The spirit of our people is high… .”

Pushing north from El Paso, where he had temporarily headquartered, Sibley led his troops up the Rio Grande Valley in the teeth of a punishing winter storm. As one Southern soldier reported:

“The sleet was enough to peel the skin off your face.”

By Feb. 16, Sibley’s Brigade was in sight of Fort Craig. The Texans went into camp about five miles below the post while Sibley and his officers assessed the strength of the federal bastion.

Four days later, the Confederate commander decided he could not afford the casualties that a frontal assault on the powerful fort would bring. He ordered his brigade to cross to the east side of the Rio Grande in a bid to bypass the post and draw the Union forces out.

Canby stood on the porch of his quarters at Fort Craig on the morning of Feb. 21 and watched the long gray line of Confederate troops moving up the river on the opposite shore, he took Sibley’s bait and ordered the bulk of his forces out of the post to intercept the Rebels. Three companies were left behind to protect the fort.

About two miles north, near the base of the long volcanic escarpment of Mesa de la Contadera, also known as Black Mesa, the federals forded the river and attacked. The result was the Battle of Valverde, named for the small river valley in which it was fought.

For two days the Union and Confederate forces waged a furious fight in which the two armies maneuvered, charged and counter-charged before the federals were defeated and fled to cover behind the walls of Fort Craig. Union forces suffered a reported 263 dead, wounded and missing, while the Texans listed total casualties of 187 men.

Although Fort Craig itself was untouched and most of its garrison survived, Valverde was a tactical victory for Sibley, who now was free to strike north toward Albuquerque and Santa Fe. In early March, his brigade captured both towns. In the final analysis, however, Valverde would prove to be a strategic error for the Texans, and Sibley would reap bitter fruit for leaving an unconquered Fort Craig in his rear.

In assessing Canby’s failure to stop the invaders at Valverde, a Union staff officer, Capt. Gordon Chapin, in a report to Maj. Gen. H.W. Hallack, Army chief of staff in Washington, blamed the instability of the militia forces. Some had turned and swiftly fled from the battlefield in the face of the Confederate attacks.

At the same time, Chapin had high praise for Canby:

“Col. Canby did everything that man could do … to save the day. He beseeched and begged, ordered and imperatively commanded … and a deaf ear met his supplications and commands.”

Theo Noel, a Confederate cavalryman, was jubilant: “We carried everything before us, routing the enemy. We drove them to the river, where they took to the water on short notice, more like a herd of frightened mustangs than men.”

A notable exception was 25-year-old Capt. Alexander McRae, a West Pointer and native of North Carolina who had remained loyal to the Union and been ostracized by his family for his stand. McRae commanded a Union artillery battery at Valverde and died at his guns when the Confederates overran his position. An account of the battle published in the St. Louis Republican on March 23, 1862, cited McRae’s bravery:

“With his artillerymen cut down, his support either killed, wounded or flying from the field, Capt. McRae sat down calmly on one of his guns, and with revolver in hand, refusing to flee or desert his post, he fought to the last.”

McRae, for whom a later-day New Mexico Army post would be named, was buried in the Fort Craig cemetery. In 1867, his body was removed and enshrined at his alma mater, West Point.

With his triumph at Valverde and the capture of Albuquerque and Santa Fe, Sibley pushed on toward Fort Union, the last federal strong point blocking the way to his primary objective— the gold and silver mines of Colorado.

Unlike their brother soldiers at Craig, however, the 700 federal troops at Fort Union, reinforced by 900 Colorado volunteers, didn’t wait for Sibley to come to them. They marched to meet the Confederates in the field.

In late March 1862, they turned back the Texans in a three-day battle at Glorieta Pass, 20 miles southeast of Santa Fe. In the course of the fight, the entire Confederate supply train was destroyed in a skillful flanking attack by Union cavalry. This placed the Texans in an impossible position.

Defeated, short of food, ammunition and other supplies and plagued by a hostile civilian population, Sibley’s Brigade embarked on a long and dreary retreat down the Rio Grande Valley. Along the way, the once-confident Confederates were hounded by pursuing Union troops, who engaged the Rebels in a running skirmish at Peralta, south of Albuquerque.

When the fleeing Texans neared the vicinity of Fort Craig, Sibley paid the price of leaving the post intact. His soldiers, instead of following the fastest way home down the valley, were forced to detour through the mountains, 25 miles to the west, to avoid the fort.

As the weary Rebel army struggled through forested canyons and up timbered slopes, it nearly disintegrated. Discarded weapons, equipment and wagons marked the route of the retreating column, which stretched out for 50 miles.

Morale and discipline vanished as the Southerners trudged through the wilderness with little food or water. The fight had gone out of them. They had suffered the loss of about 1,000 men from all causes during their three-month campaign in New Mexico, and the only goal of the survivors was to reach the safety of Texas.

As one soldier confided in his diary:

“Now, it’s every man for himself.”

In the aftermath of Sibley’s defeat, the soldiers of Fort Craig returned to campaigns against the Navajos and Mescalero Apaches. By 1868, both of these tribes had made permanent peace and Indian troubles shifted to southwest New Mexico and Arizona.

For Fort Craig, it was the beginning of the end.

Garrison duty, routine patrol and boredom again became the way of life at what cavalry Capt. John Bourke in 1869 described as “a lonesome sort of a hole.”

Garrison duty, routine patrol and boredom again became the way of life at what cavalry Capt. John Bourke in 1869 described as “a lonesome sort of a hole.”

By 1879, the post had outlived its usefulness and was ordered abandoned. However, the troops had scarcely pulled out when the fort was reactivated to cope with an uprising of Victorio’s Warm Springs Apaches. A year later, Victorio was dead, killed by Mexican troops in the mountains of Chihuahua, but Craig would hang on for another five years as a supply point and troop-staging area.

It was not until July 1885 that the Army pulled out for good. When the last contingent, a caretaker force of a lieutenant and seven enlisted men, marched away, a post which had served for three decades was left to melt back into the desert from which it came.

Through the years, a number of proposals to preserve Fort Craig were made, but they came to naught. Finally, in 1981, the site came under the control of the federal Bureau of Land Management, whose archaeologists moved in to arrest a century of neglect and decay.

Today, Fort Craig is a National Historic Site. Trails lead visitors through the scattered and heavily eroded ruins atop the desert bluff that looks down on the green ribbon of the Rio Grande, a mile to the east. Most prominent are walls of the commanding officer’s quarters, the guard house and several warehouses, which an inspecting officer in 1867 described as “the best built I have seen in the district.”

Above the spacious parade ground, now grown heavy with desert plants, the American flag once again flies from a high staff. On the south side of the post, the earthen fortifications built to repulse Sibley’s army are still visible.

Despite well-managed restoration efforts, Fort Craig is a mere shell of what it once was. The desert landscape and the surrounding moutains have changed little, but the fort has succumbed to the passing years. As Capt. Charles King, a frontier officer, once put it: “It’s all a memory now, but what a memory to cherish!”

Source:

ABQjournal: Desolate Outpost. https://www2.abqjournal.com/venueold/travel/tourism/heritage_craig.htm