Like Abó and Las Humanas, red-walled Quarai was a thriving pueblo when Oñate first approached it in 1598 to “accept” its oath of allegiance to Spain. Three of Quarai’s Spanish priests were head of the New Mexico Inquisition during the 1600s, including Fray Estevan de Perea, Custodian of the Franciscan order in the Salinas Jurisdiction and called by one historian the “Father of the New Mexican Church.” Despite the horrors associated with the word “Inquisition,” records from the hearings show that the early inquisitors, in New Mexico at least, were compassionate men capable of separating gossip from what the church regarded as severe transgressions.

In one case, tensions between church and state reached a peak when Perea charged the alcalde mayor of Salinas with encouraging the native Kachina dances. That case was dropped, but the alcalde’s continued disruption at the mission prompted the Inquisition to banish him. Quarai was the base of operations for the Inquisition here in New Mexico.

Testimony recorded by Perea and others for trials at Mexico City provides a valuable picture of Spanish Indian relationships in the 1600s. Spain’s sophisticated legal system was applied (when it worked as intended) to protect the Indians’ civil and property rights. And perhaps the Spanish colonists learned the patience and endurance that the Pueblos had practiced for hundreds of years.

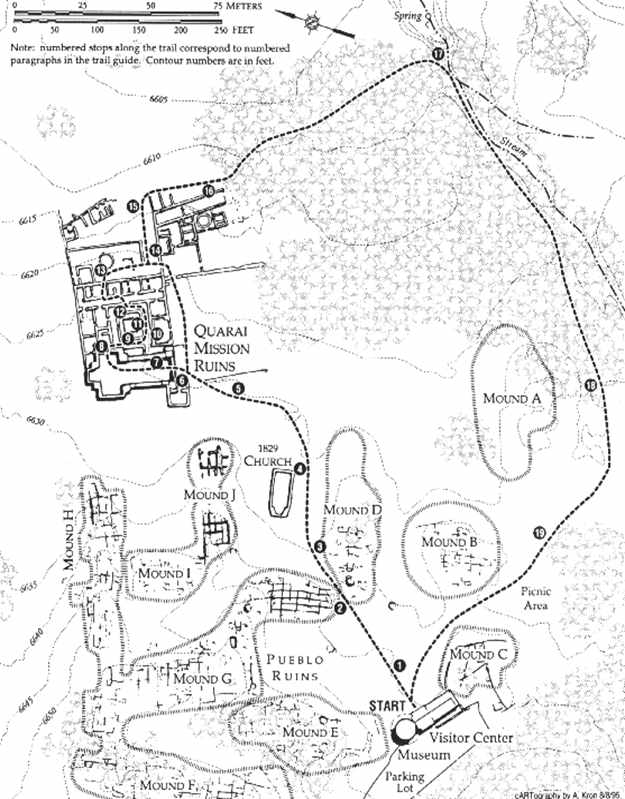

The “hills” around the ruins are the remains of a large masonry Indian village or pueblo. The few scattered walls above ground resulted from limited excavations in the 1950s. There has been little archeological research in the pueblo, so we have only the barest outline of Quarai’s prehistory. From ground surveys of the area and the occasional mention in Spanish records, we believe that the population of Quarai in the 1600s was around four hundred to six hundred people. Not all of the house blocks were occupied simultaneously; some were abandoned while others were thriving.

Quarai was on the southeastern fringe of the pueblo world. Tiwa-speaking Indians migrated through mountain canyons from the area around present-day Albuquerque before A.D. 1300. They established settlements along the eastern slope of the Manzano Mountains at Chilili, Tajique, and Quarai. They farmed, hunted, and gathered salt from saline lakes in the valley beyond. They also took advantage of their location between Rio Grande pueblos and the Plains Indians to become traders.

Today in New Mexico, the Tiwa language is still spoken at the pueblos of Taos, Picuris, Sandia, and Isleta.

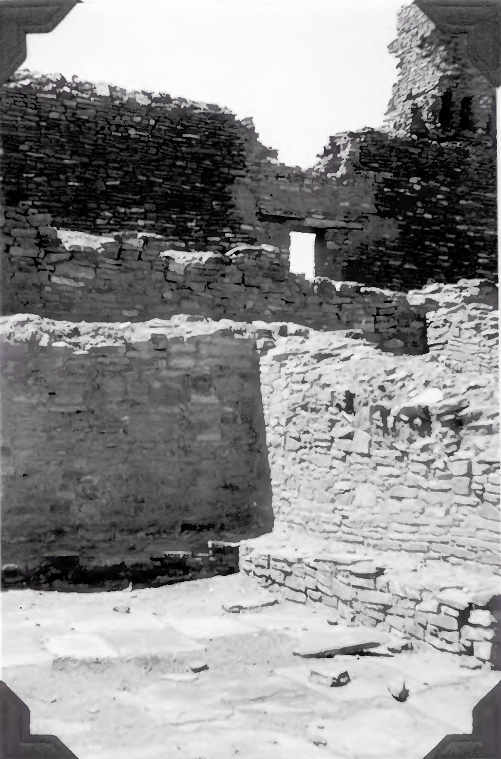

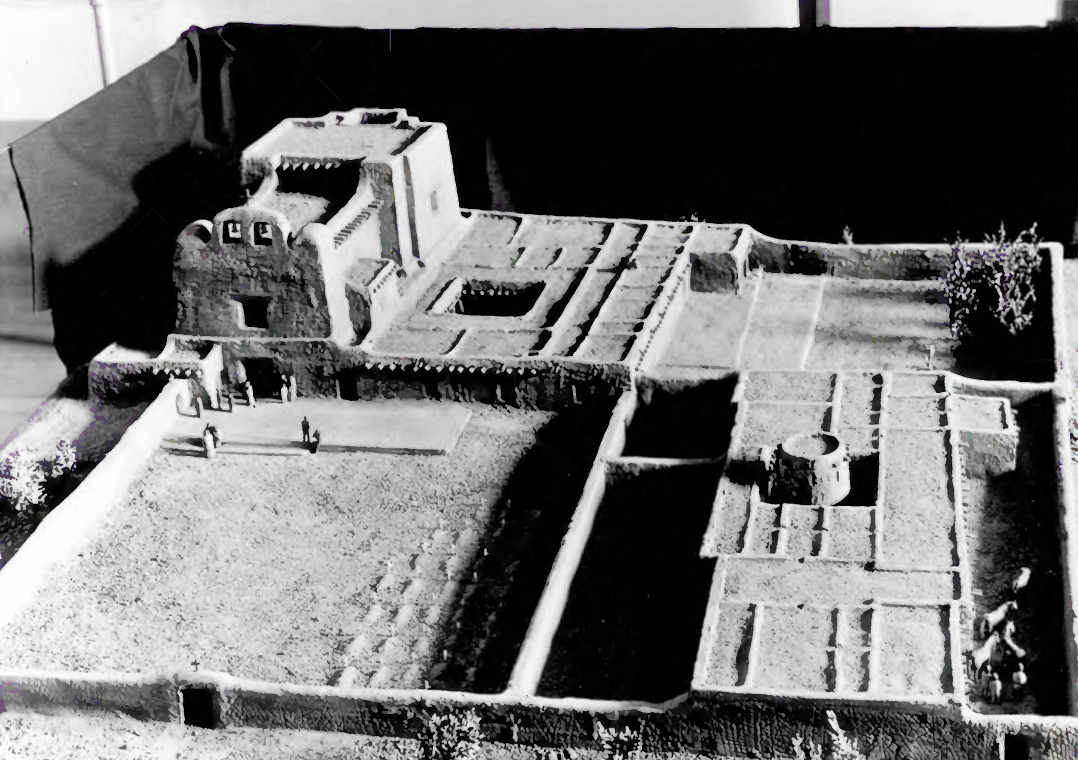

Also called the church of Nuestra Senora de La Purisima Concepcion de Cuarac, enduring symbol of the early Spanish presence in this valley. Quarai is probably a later phonetic spelling of Cuarac. Once protected by adobe plaster, the red sandstone walls are forty feet high on foundations seven feet deep and six feet wide. The interior length of the church is one hundred feet. The nave is twenty-seven feet wide, and the transept fifty feet. Since we have no plans or drawings of these early Franciscan missions, we must envision how they looked by studying the physical clues. The square holes above the entry are sockets for beams. They hint that a porch extended across the front of the church, although no traces of it remain. The splayed entrance held wide doors which swung inward on iron pivot hinges providing light and easy access.

Fray Juan Gutierrez de la Chica was the priest here in 1628, and he probably started the church’s construction. Although Quarai was on a frontier, remote from the hearth of the Spanish Empire and the Catholic Church, every detail of the church’s conception and construction reveals careful planning and attention. These massive stone walls enclosed a vast space that contrasted sharply with the modest rooms familiar to the Indians.

From the Park Service Pamphlet

You are directly beneath the choir loft. The square sockets that held the outside porch roof also held the floor joists of the choir loft. On their opposite end, the joists were supported by a large square beam fitted into the single sockets on the side walls. The low ceiling thus formed created an antechamber. Initially, the baptistery was located here. The large opening high on your right was the choir loft entrance. Access was from a second-story room with a landing outside the entry.

At your feet is part of the original flagstone floor. The walls, plastered white, had painted dados at waist height. Typically the dados were bands of stripes and patterns painted in red, black, yellow, and blue. Above them, religious paintings hung along the walls.

Continuing into the nave, the ceiling height soared to the top level of the rectangular sockets high along the side walls. Parishioners assembled here for mass. Toward the front, this space opens out into the side arms of the transept and then narrows again to form the apse. The overall shape of the church was that of a cross. In each arm of the transept, there was a small altar. The main altar was centered in the apse with three steps leading up to it. The side altars were at floor level.

Look again to the top of the church walls. The long narrow sockets held corbels and vigas or roof beams. Corbels were the carved and painted supports for the long beams that spanned the church’s width and supported the ceiling. Notice that the sockets in each church area–nave, transept, and apse-are at different heights. This difference visibly emphasized the three parts of the cruciform church.

The variance in height between the nave ceiling and the higher transept ceiling allowed for a transverse clerestory window. This window extended across the width of the church to the point where the transept arms cross the nave. The southern exposure caused a broad light to illuminate the sanctuary and altar.

The altar is raised high and bathed with lights the cynosure of the church and religious services. Although supplies were difficult to get in this remote corner of the Spanish Empire, altars usually had lavish furnishings. Shipping records of the Mission Supply Service list Rouen altar linens, brass candlesticks, incense burners, chalices, and paintings of patron saints. Retablos reached almost to the ceiling behind the main and side altars.

They were decorated with richly painted carvings, bits of reflective mica, statues, and small portraits of saints. These items were probably made in Mexico, disassembled, and shipped to the mission. Against the white plastered church walls, the altars stood out in lush detail.

The kiva is a ceremonial chamber of the pueblo religion. This kiva is a shape more familiar to us than the square kiva in the patio of the convento. However, in Tiwa pueblos, both square and round kivas are typical. The flat roof of a kiva was supported by posts. On the floor was a fire pit, and the hatchway above served as both an entrance and an opening for smoke to escape. As warm air and smoke rose out the hatchway, cool air descended through a ventilator shaft on the east side. Thus fresh air circulated through the kiva, making it a reasonably comfortable place for the various activities carried out below.

This kiva was here before the church and convento were built. It was buried by mission construction, implying that the Spanish structures were built on a mound of pueblo ruins similar to those you see along the trail today. It was never in use during the mission period.

The architectural contrast between these Tiwa and Spanish structures is clear, and it suggests an even greater gulf between the social and spiritual worlds of the cultures which created them. Yet, oddly enough, this is where we obtained the majority of our unusual readings.

By the 1670s, the people of Quarai were suffering all the problems of drought, disease, famine, and hostile tribes that plagued the Salinas Jurisdiction as a whole. The drought and famine continue. Many are sick, and some are dying. I am giving charity to the natives. Provisions stored for just this case are pitifully low. We have received more cattle and other provisions for the Spanish Soldiers and the natives. The terror and outrages continue. Some are leaving every day. Fray Francisco de Ayeta, the procurator general and the custodian of the provinces of New Mexico was to bring us carts of supplies and reinforcements. Still, I have decided that we can wait no longer. We must leave all two hundred families and go north to Tajique, where there is a mission and settlement. If that, too, is unprotected, we will go on to Isleta to be with other Tiwa speakers.–Fray Diego de Parraga.

Quarai before Excavation and Stabilization

Sources:

Investigation of Quarai Mission – SGHA. http://www.sgha.net/nm/Quarai_Mission.pdf