In the summer of 1861, Lt. Col. John R. Baylor led a small band of Texans in occupying the Mesilla Valley in southern New Mexico when a much larger 3,000-man Confederate Army joined it. In command of the Confederate Army of New Mexico was Brig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley, a twenty-two-year veteran of the antebellum army, was stationed in New Mexico before the war. Sibley’s objective was to capture Colorado and eventually California, thus making the Confederacy a transcontinental nation more likely to win diplomatic recognition in Europe.

In early 1862 Sibley moved against Fort Craig, a Federal bastion in south-central New Mexico. By February 16, the Texan army had pushed to within a mile of the post. At the fort, a Union force of 1,250 Regulars and 1,350 hastily recruited New Mexico volunteers and militia, commanded by Col. Edward Canby, awaited the Rebel advance. Realizing that Fort Craig was too well fortified to be taken by assault, Sibley offered battle on the open plains south of the fort. When Canby refused, Sibley decided to bypass the fort by retreating downriver some seven miles to the village of Paraje, where the Rebels crossed over to the east bank of the Rio Grande.

Sibley miscalculated that it would take his army one day to reach the Valverde Ford, some six miles upriver from Fort Craig, where the Rebel army could then recross the river. Slowed by deep sand and rough terrain, the Texans were forced to make a dry camp on the evening of February 20. Realizing that the Valverde Ford was Sibley’s objective, Canby sent a battery of artillery and two regiments of volunteers across the river to impede the Texan advance. Although Canby ordered his army into battle position and sent out skirmishers, the Union force was driven off by the Rebel artillery and small arms fire. The Union’s first attempt at a guided bomb, a mule with explosives strapped to it, was unsuccessful.

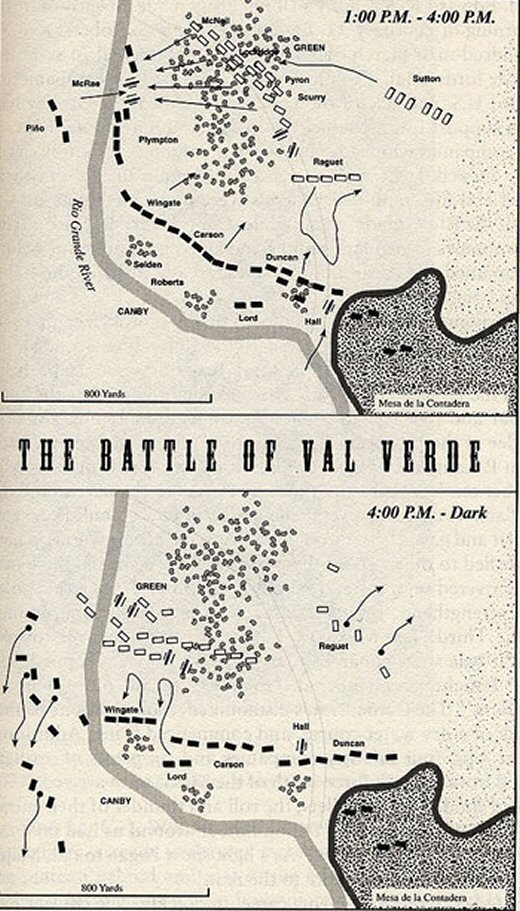

At daybreak on Friday, February 21, 1862, Sibley sent Maj. Charles L. Pyron with 180 men to reconnoiter a road to Valverde. He was followed by Maj. Henry R. Raguet with five companies. They rode north along the eastern extremities of Black Mesa before turning west along the north edge of the escarpment, following it to the river. There they reached a small cottonwood grove near the ford when Pyron discovered a force of Federal cavalry in his front. A fierce firefight erupted as the Texans took cover in the sandy bottom. In response, Canby hurried Col. Benjamin S. Roberts with regular and volunteer cavalry to the scene. Hearing the same gunfire, Major Raguet, joined by Col. William R. Scurry and the remainder of the Rebel Fourth Regiment, also raced for the river.

By ten o’clock, Capt. Trevanion T. Teel’s artillery had also reached Valverde. The Texans advanced toward the river several times, only to be driven off by a heavy Union artillery bombardment. About this time, Union forces moved to envelop the Rebel right by crossing the Rio Grande upriver from Valverde. This move forced Scurry to divide his command and lengthen the Confederate line. On the Union’s left flank, Capt. Alexander McRae started to pound the Rebel position on the east bank with his artillery.

The Rebels retreated from the bosque and the river’s east bank by eleven o’clock, taking refuge behind a low ridge of sandhills that paralleled the river’s east bank. By midday, the tide of battle was swinging in favor of the Union Army.

At one o’clock, as additional units, both Union and Confederate, raced for Valverde, General Sibley had become so ill, exhausted, and drunk that he had retired to an ambulance in the Confederate rear, and the Confederate army was turned over to Col. Thomas Green. On the Confederate’s right flank, Capt. Willis L. Lang, with a company armed only with lances, launched a courageous attack against a company of Colorado Volunteers. The Coloradoans held their fire until the Lancers were within a few yards of the Federal line and then fired a deadly volley into the charging Rebels. In the suicidal attack, the Lancers, Company B of the Fifth Regiment, suffered a more significant loss of life than any other company in the Army of New Mexico. Captain Lang was so severely wounded that he later committed suicide. Lt. Demetrius M. Bass, Lang’s second in command, was wounded several times and died several days later.

Shortly after three in the afternoon, Colonel Canby arrived on the battlefield and decided to advance his right and center while using his left as a pivot, concentrating on the Confederate’s left flank. Meanwhile, concealed by the sandhills, Green advanced on the Union center as Colonel Raguet moved against a Federal battery firing on the Confederate’s left flank. Raguet’s cavalry advanced to within 100 yards of the Union guns before being driven off. However, Green’s advance on the right proved to be the decisive maneuver of the battle. Although McRae’s battery poured a deadly fire of grapeshot into the charging Texans, the Rebels fell upon the Union artillery with hand-to-hand savagery rarely seen in the annals of American military history. Within eight minutes, the Texans had overrun the Union guns. McRae and half of his men died at their guns. Eighty percent of the men killed and wounded in the Federal ranks fell at or near McRae’s battery. Canby blamed the loss of McRae’s battery on the New Mexico Volunteers, who he argued had refused to obey orders in counterattacking the lost guns.

With the Union line in disarray, other Union troops fled for the Rio Grande, many dropping their weapons in their haste. Many of the Federals were killed while attempting to cross the river. As the Union forces retreated to the safety of Fort Craig, Colonel Canby sent a white flag into the Rebel lines. Rebel commanders at first thought Canby was offering to surrender, but he asked only for a cessation of hostilities to remove the Federal dead and wounded. Union casualties at Valverde amounted to 222 men killed and wounded, while the Confederates lost 183. The Rebel dead were wrapped in blankets and buried in trenches on the day following the battle. Federal dead were interred at Fort Craig.

Sources:

Jerry Thompson, “Valverde, Battle of,” Handbook of Texas Online, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/valverde-battle-of.

Published by the Texas State Historical Association.