The battle scene between Union and Confederate forces occurs in the famed Clint Eastwood western, The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly. The battle is intended to personify the Battle of Peralta and the New Mexico Campaign in general, though obviously exaggerated.

Though no specific year or date is stated in this movie, at least part of it occurs during the New Mexico Campaign of 1862. This is confirmed when the hotelkeeper and Tuco mention the retreating Confederate General Sibley (real-life Henry H. Sibley) and the advancing Union Colonel Canby (another historical person: Colonel Edward Canby). This is consistent with the campaign that took place between February and April 1862 in the Union territory of New Mexico and the Confederate state of Texas. So, here is some exciting information about the actual battle.

Most people simply don’t realize how many Civil War battles were fought west of the Mississippi River, nor how many were fought in New Mexico. New Mexican residents enlisted in volunteer regiments or were enrolled in local militia units. When their enemies arrived, many of these amateur soldiers and territorial officials got a view of the destructive potential of nineteenth-century warfare. Other New Mexicans living along the Rio Grande valley often experienced that destruction first hand. Among them were those living in the tiny village of Peralta, roughly twenty miles south of Albuquerque. At the time of the Civil War, the village of Peralta included about two miles of adobe buildings, various enclosures, cottonwood groves, and irrigation ditches. It was also the residence of the Territory’s chief executive, Gov. Henry Connelly.

A wealthy merchant and long-time resident of New Mexico, Connelly had married the widow of former governor Mariano Chavez. Thus, he acquired extensive land holdings in the Rio Grande valley. These included a large house and adjoining fields north of Peralta’s main village and church. Twin rows of giant cottonwoods lined the lane leading up to the plantation-like mansion.

Cool Fact:

The stumps of these trees are still visible along part of the lane. However, the house was eventually torn down to accommodate more recent residences and businesses.

Unfortunately, his property would become the site of the Battle of Peralta during the final stages of the Texan invasion of New Mexico. After the Confederate Army was defeated at the Battle of Glorieta on March 28th, 1862, General Sibley was faced with the prospect of starvation after his supply train was destroyed. The only option left for him was to retreat back to Texas. But, of course, this meant that he would have to fight his way back through the Union forces at Fort Craig. Unfortunately, however, things were about to get much worse.

While the defeated Confederate Army was convalescing in Santa Fe, they learned that Colonel Canby, the Commander of Fort Craig, had left Colonel Kit Carson and his New Mexico Volunteers to guard the fort. Canby had taken twelve hundred men and four cannons and headed north to intercept the Confederates. But, before he departed, he ordered another twelve hundred troops to move south from Fort Union to link up with his force.

The Federals made a diversionary attack toward Albuquerque, firing on Confederates guarding the few supplies stored there. This would eventually be called the skirmish of Albuquerque. Canby’s artillery opened fire at long range from the edge of town for two days. The Union artillery ceased firing when a local citizen informed Canby the Confederates would not permit the civilians to seek shelter. Canby felt he had accomplished his mission; he knew the Rebels were still willing to put up resistance. The Union demonstration also caused Colonel Tom Green to hastily pull out of Santa Fe and move to Sibley’s aid, hoping to counter-attack in the morning. Undercover of darkness Canby’s forces slipped away without the rebels’ knowledge.

The Federals made a diversionary attack toward Albuquerque, firing on Confederates guarding the few supplies stored there. This would eventually be called the skirmish of Albuquerque. Canby’s artillery opened fire at long range from the edge of town for two days. The Union artillery ceased firing when a local citizen informed Canby the Confederates would not permit the civilians to seek shelter. Canby felt he had accomplished his mission; he knew the Rebels were still willing to put up resistance. The Union demonstration also caused Colonel Tom Green to hastily pull out of Santa Fe and move to Sibley’s aid, hoping to counter-attack in the morning. Undercover of darkness Canby’s forces slipped away without the rebels’ knowledge.

The following morning, Colonel Canby moved his men east through Tijeras Canyon and joined the Fort Union troops near the village of San Antonio (now called Cedar Crest). Then he moved his command, numbering about twenty-three hundred men with an additional artillery battery from Tijeras Canyon.

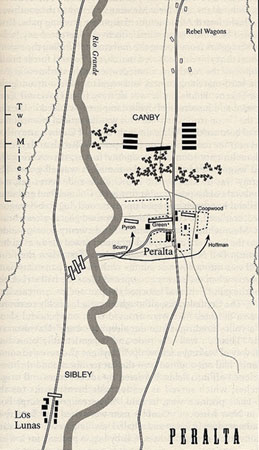

After burying eight small howitzers for which they had no draft animals, most of the Confederate troops crossed the river near the present-day Barelas Bridge south of Albuquerque’s Old Town. Progress along the sandy roads was slow, and Colonel Green decided to march his regiment south along the east side of the Rio Grande, parallel to Sibley’s other units, and rejoin after crossing at a good ford near Peralta. Green found himself near the governor’s house at nightfall on April 14th and decided to camp there and cross the following morning.

The Union troops emerged from Tijeras Canyon on the same day by late afternoon. They marched all night southwestward along the old road that crossed present-day Kirtland Air Force Base and the Isleta Reservation. Aided by mild weather and bright moonlight, Canby’s men covered thirty-six miles that day. By three o’clock the following morning, they finally left the sandhills. They camped in the bosque about one mile northeast of Peralta, near the Connelly mansion where the Col. Thomas Jefferson Green’s Fifth Texas Mounted Volunteers had positioned themselves. The other Texans had camped on the west side of the Rio Grande, near Los Lunas, three miles from Peralta.

To the amazement of the Union Soldiers, the Confederates were having a celebration. Fiddle music and the occasional crash of glass and wood could be heard coming from the governor’s house.

One Union artillerist, Lt. J. M. Bell, remembered that;

“the sounds of the fandango carried into the morning hours,” and that “all was merry as a feast within the dark outline of the town, just growing visible in the gloomy light of approaching day.”

No Confederate outposts or sentries were encountered, and the Union troops waited for the dawn to execute an attack. Separated from Sibley by the river, the Fifth Texas was unaware that Canby’s impatient soldiers waited nearby.

However, Canby thought that the ground the Texas troops held was too strong to be taken efficiently, even though his men outnumbered the enemy five to one. The ditch banks and low adobe walls that enclosed the fields around the Connelly mansion formed strong natural fortifications. Several Confederate cannons were also within the maze of fields. However, before the order to attack could be given, a Confederate supply train approached from the north.

A party of mounted Colorado Volunteers intercepted the Texan supply train, forcing them to surrender. One Union soldier was mortally wounded, and four Confederates were killed in the skirmish, which saw the wagons captured and the howitzer it was carrying turned against its former owners.

As the Colorado Volunteers returned from this fight, an independent company of New Mexico Volunteers (Graydon’s Spy Company) dashed into Peralta, fired a few shots, and retired. Canby then opened fierce artillery fire on the Texans around the governor’s house.

The cannonade looked and sounded grand, especially when the sizeable twenty-four-pounder howitzer fired. Still, the soft ground and adobe walls absorbed much of the impact of the shot and shells. However, the Texans were not injured. Instead, Green responded with a cannon barrage of his own, which killed two of Canby’s soldiers and several draft animals, but otherwise accomplished very little. Infantrymen from both sides exchanged musket shots at long range throughout the day. However, Canby still would not risk a direct attack on the Connelly mansion. Instead, he sent separate columns under Colonels Gabriel Paul and John Chivington around to the north and west of Peralta to prevent Confederate reinforcements from arriving.

During this encircling movement, the Union troops skirmished with Green’s men and marched south near present-day West Bosque Loop. They turned back a relief column that Sibley led, just as it was emerging from crossing the river. However, there was little action except for the continuing crash of artillery. The Confederates’ artillery fire on the Union troops moving around their positions typically went over their heads. In addition, the Texans had expended most of their explosive shell ammunition earlier during the campaign. So their artillery was not very effective against troops. No more Federals were killed during the battle. Likewise, the Texans reported only two wounded in addition to those lost during the morning wagon train attack. However, the cottonwood groves north of Peralta were obliterated.

Sibley led the 4th and 7th Texas Mounted Rifles across the river. The rival armies battered each other in an artillery duel until a dust storm blew in and allowed the Confederates to withdraw to the west bank of the Rio Grande, leaving behind a town that had been reduced to rubble.

The Confederates reached Los Lunas at 4 a.m., where they rested for a few hours before continuing their retreat. Canby followed with the Union army, harassing the Confederate column with cavalry.

In the center of the battle, the Connelly house received severe damage from the Federal artillery and musket fire. Ditch bridges, field enclosures, and outbuildings around the mansion were battered.

Governor Connelly was naturally pleased with the military results of the Battle of Peralta. Still, he was furious about the destruction of his property by the Texans. After returning the territorial government to Santa Fe, Connelly visited his mansion a month after the battle. He claimed more than $30,000 worth of damage to his residence and surrounding property. The Texans were, the governor claimed, “devoted to the destruction of everything of value about the premises. The same would have happened . . . to my neighbors of Peralta had it not been for the timely arrival of General Canby…;.”

He was especially incensed over the destruction of household goods and furniture, for which the Texans could have had no use, and over damage to the nearby village. It was some time before Henry Connelly was sufficiently calm to see these sacrifices as part of the final Union effort to rid New Mexico of its Confederate invaders. The last battle of the Civil War in New Mexico thus ended, being one of the least bloody on record.

In summarizing their New Mexico campaign, Governor Connelly observed, “This is the second invasion our Territory has suffered from Texans, both of which have proved equally disastrous [to them], and it is hoped we will never witness another.”

Sources:

New Mexico Historical Review, Volume 58, #4 (1983)

Battle of Peralta